n* o * r * t * H * n * e * s * s

*

first, it seeks the highest place;

second, it suffers not for company;

third, it holds its beak in the air;

fourth, it has no definite color;

fifth, it sings sweetly.

These traits must be possessed by the contemplative soul.

It must rise above passing things, paying no more heed to them than if they did not exist. It must

likewise be so fond of silence and solitude that it does not tolerate the company of another creature.

It must hold its beak in the air of the Holy Spirit, responding to his inspirations, that by so doing it may become worthy of his company.

It must have no definite color, desiring to do nothing definite other than the will of God. It must sing sweetly in the contemplation and love of its Bridegroom.

~ The Sayings of Light and Love #121 by St. John of the Cross

The north star is the heart of heaven and earth,

When the heart is nurtured by openness,

It thereby becomes still;

When energy is nurtured by openness,

It therefore circulates.

When the human mind is calm and quiet,

Like the north star, not shifting,

The spirit is most open and aware.

(Taoist poem)

The Hut of Clarity

My hut is not an abode of idleness.

Ordinary people are not allowed

To see it on a whim.

The world therein has always been vast;

The space outside is not really large.

If you ask the master what he does,

I reply that he faces south

To gaze at the north star.

(Taoist poem)

'You do not have to sit outside in the dark. If, however, you want to look at the stars, you will find that darkness is necessary. But the stars neither require nor demand it' (Annie Dillard 1988: 31).

I seldom really see it. I'm too busy. Yet sometimes, as unexpectedly as a sudden breeze billowing the curtains, it gathers my attention, filling me with its dark presence. It must have spoken to someone else, too, for whoever built this quiet little cottage left a notch in the eves of the roof, allowing a gray branch to gnarl its way skyward unobstructed. Evidentially the architect miscalculated, and the carpenter simply compensated in favor of the oak, disfiguring the roofline rather than the integrity of the living form.

Just down the hill stands another oak, agonized, twisted, yet flourishing. It is framed by a vast window, inside of which a man, carved from oak, hangs. He dangles limply from a cross, his back to the window and the great tree. People come to this little stone chapel to dance and sing, to sit quietly, to play music, and to pray--sometimes, I think, more to the tree than to the oaken figure that seems to merge with it.

Oaks abide. And abiding they are revered, for they reveal that which abides within us. What frequenter of oak groves at dusk has not felt the abysmal power of their stillness and borne it secretly away into the night? Oaks abide, and oaks are prayers -- their dark hearts leafing outward into the light as surely as human hearts flower inward, following the grain of an even fuller illumination.

Like oaks, words that embody the abiding endure through vast reaches of space and time. In fact, our words "truth," "trust," and "tree" can all be traced back four thousand years to an ancient Proto-Indo-European word for the tree that to them was the Truth. That tree was the oak. They called the oak *dorw, which also meant "firm," "strong," "enduring." The oak is, after all, a stout tree, as anyone who has cut through oakwood can testify.

The word "Druid" is also from the *dorw family. The Druids were a priestly class of bardic seers endowed with visionary powers. The name itself means "seer of oaks," and one wonders what they saw that would give them such a title, for a seer is one who perceives forms not available to the perception of the common eye.

One thing is certain. The oak had a special meaning not only for the Druids, but for the Indo-Europeans as a whole. During the warm period around 2000 B.C., before the dispersal of the Proto-Indo-European tribes, grand oaken forests covered most of Europe, extending hundreds of miles north of their present thermally mandated boundary. Giant oaks, much larger than any present-day specimens, were a source of food (in the form of acorns) and religious inspiration. These trees so impressed the Proto-Indo-European consciousness that the oak became established as the formal religious symbol of the era. Because it revealed the abiding, it was a symbol of great durability and power. In fact, if one traces the descendants of the Proto-Indo-European oak word in the various Indo-European languages, from Ireland to India one finds they are represented prominently in religious usage. This tree was, as we have noted, the Truth.

All the Indo-European High Gods were bearers of the thunderbolt, and were called Thunderers. It is natural that the oak was sacred to each to them, because it is struck by lightning more often than any other tree. It channels the power of the Thunderer to Earth.

Thus the Balts burned fires in sacred oak groves to their God of Thunder. The Teutons ignited holy oakwood fires in honor of Donares Eih, their Thunder God. The Greeks felt that sounds coming from the oak were oracular, the voice of Zeus, the Thunder Bearer. The tribes of ancient Italy maintained perpetual oakwood fires watched over by vestal virgins, and Jupiter was worshipped in the form of an oak. The Celtic Druids ate acorns, worshipped in sacred oak groves, lighted oakwood fires, and praised the Celtic High God in the form of an oak. What was it, we ask again, that these seers of oaks saw?

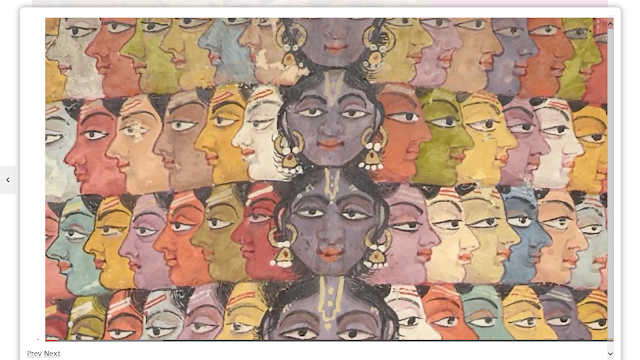

Turning now to India, the Sanskrit relatives of the ancient Proto-Indo-European term for oak (*dorw) provide the answer. The most obvious relative is daru, "tree." In ancient cultures trees had not yet come to be valued as board feet of lumber. Extending into Heaven the tree represented the immeasurable Truth, the Cosmic Pillar, the Axis of the World. Around it the entire universe was thought to revolve, just as the constellations circle Polaris, the North or Pole Star. In fact, like the star-crowned Christmas tree, the Cosmic Tree is often depicted in ancient myths and art as crowned with the Pole Star.

When the Aryan tribes spilled over the mountain passes of the Hindu Kush into the fertile river valleys of northern India, they entered an alien climate, leaving behind the great oaken forests of their homeland, far to the north. Yet northern India was not devoid of oaks. In fact, one of Buddha's appellations, Shakyamuni, means Sage of the Oak Clan (the Scythians). The Aryan tribes, however brought with them another relative of *dorw that retained in its sound and meaning something of the forgotten sacred oaks of their ancestry. The Sanskrit word is dhruva, and it means "the abiding, the firm, or fixed one." It is also the name of the star that abides like the oak, the Pole Star, Polaris. And it was dhruva, the Pole Star, that became a subject for Patanjali, one of India's greatest seers and teachers. He lived around 500 B.C. and left us sort of a lab manual, the Yoga Sutras, a work of concise and precise formulas (surtras) facilitating the systematic unfolding of consciousness (yoga).

The third chapter of this treatise is concerned with subtle, supernatural powers (siddhis). Formula 28 of this chapter states that "by performing samyama on the Pole Star (dhruva), one gains knowledge of the motion of the stars."

Now this seems obvious enough. After all, shepherds, sailors, astronomers, and lovers -- in fact, anyone having normal vision and residing in the Northern Hemisphere -- has the ability to observe the nocturnal heavens rotating around the North Star. The only perplexity is that Patnjali, a writer of great precision and economy of expression, should list this as a subtle, supernatural power. Perhaps this meditation on the abiding star has something to do with why the Druids were called seers of the abiding tree.

The key to this riddle is in the world samyana, which has no equivalent in English. According to Patanjali, however, the term designates a technique of meditation in which three qualities of consciousness merge. These three qualities are (1) the abiding, (2) the flowing, (3) the uniting.

1. The abiding is fixity or duration of attention on an object. This does not simply mean staring, for even if we stare fixedly at something we experience delicate lapses of attention. This abiding quality is involved in every act of attention, but it seems that the Pole Star, and oaks -- or even the ideas of them -- are naturally unmoving and have the ability to draw us into the depths of the abiding. In fact, the Sanskrit term for this abiding quality of consciousness is another word derived from the ancient Proto-Indo-European oak word *dorw. The Sanskrit term is dharana. As Martin Heidegger said: "To think truly is to confine oneself to a single thought which one day stands still like a star in the world's sky." This standing still of thought is dharana.

2. Attention cannot be forcefully fixed upon an object for any great duration. The mind spontaneously flows from one act of attention to the next. However, if the mind is quiet, peaceful, and thus spontaneously concentrated, it can flow uninterruptedly toward any object. It flows abidingly. Flowing and nonflowing coexist. The Sanskrit term for this flowing quality is dhyana, and it, too, is involved to a minor degree in every act of attention.

3. Finally, when the attention flows so strongly and fixedly toward an object that it abides totally in the object and merges with it, a state of identity or unity with the object is experienced. This is called samadhi. In the purest form of samadhi, awareness has no object of attention. Consciousness is simply absorbed within its own unbound, blissful nature. In this state of peace, should the attention be directed toward any object, it would flow toward it and remain fixed in it without effort. Through this unity, knowledge of the object dawns. This unifying aspect of consciousness is also present, to some extent, in every act of attention.

Samyama, again, is the meditation in which these three qualities of abiding, flowing, and uniting merge in a powerful act of attention. They merge to a much lesser degree of effectiveness in every act of attention. The goal, then, is not to replace the normal act of thinking with some extraordinary act, but, though meditation, to reveal the full intensity and power of which every act of attention is capable at its deepest level. Though Patnjali does not tell us how the technique of samyana is actually accomplished, something of it can be suggested by a visual analogy.

The starlike diagram above has long been meditated upon in India. Contemplating it produces a flowing quality. Like an oak, this seemingly static design is capable of revealing profound depths--when internalized.

Patanajali's formula contains two phrases. There is an instruction: "By performing samyama on the Pole Star . . ." And there is a predicted result: "... one gains knowledge of the motion of the stars."

Until recently, we had no way of knowing what Patanjali meant by "knowledge of the motion of the stars." In January 1981, however, a paper appeared that promises to have farreaching influence. It presented the results of an experiment performed on the formula in question. The technique samyama was taught to hundreds of subjects from around the world who were already skilled in gaining samadhi. Their experiences were recorded. Dr. Jonathan Shear, who conducted the research, states that taking Patanjali at face value one would expect to perceive the motion of the stars in the context of the heavens as we are accustomed to perceive and think about them. And, in fact, such perceptions do represent early phases of the experience produced by the technique in question. But in many cases the experience quickly develops into something quite different. The pole-star is seen at the end of a long, rotating shaft of light. Rays of light come out from the shaft like the ribs of an umbrella. The umbrella-like structure on which the stars are embedded is seen rotating. Along the axis of light are other umbrella-like structures, one nested within the other, each rotating at its own rate, each with its own color, and each making it own pure and lovely tone. The whole experience is described as quite spectacular, blissful, colorful, and melodious.

Until recently, we had no way of knowing what Patanjali meant by "knowledge of the motion of the stars." In January 1981, however, a paper appeared that promises to have farreaching influence. It presented the results of an experiment performed on the formula in question. The technique samyama was taught to hundreds of subjects from around the world who were already skilled in gaining samadhi. Their experiences were recorded. Dr. Jonathan Shear, who conducted the research, states that taking Patanjali at face value one would expect to perceive the motion of the stars in the context of the heavens as we are accustomed to perceive and think about them. And, in fact, such perceptions do represent early phases of the experience produced by the technique in question. But in many cases the experience quickly develops into something quite different. The pole-star is seen at the end of a long, rotating shaft of light. Rays of light come out from the shaft like the ribs of an umbrella. The umbrella-like structure on which the stars are embedded is seen rotating. Along the axis of light are other umbrella-like structures, one nested within the other, each rotating at its own rate, each with its own color, and each making it own pure and lovely tone. The whole experience is described as quite spectacular, blissful, colorful, and melodious.

What is important to note is the precision of Patanjali's expression. The experience described, like the result of any scientific experiment, is repeatable, and is specific to the meditation on the Pole Star formula. Moreover, none of the subjects had any prior knowledge of the structure. They were all taken quite by surprise, for they never imagined that anything of the sort existed until the moment they experienced it. "The experience," says Shear, "is the innocent by-product of the proper practice of the technique. The logical conclusion is that the specific content of the experience represents the mind's own contribution arising in response to the practice of the technique. This is, the technique enlivens specific, non-learned or innate responses, innate cognitive structures, and allows us to experience what can, I think, properly be called an innate archetype or structure of the human mind."

This is an important point, for it demonstrates that no particular result was sought after. The experience was an innocent and spontaneous response of the mind to a given stimulus.3

Heidegger wrote that "to think truly is to confine oneself to a single thought which one day stands still like a star in the world's sky."

The Rigveda provides a similar statement:

On top of the distant sky there stands

The Word, encompassing all.

Dhruva, besides meaning Pole Star, can also signify a cow that stands still while being milked, the Word that stands still in the sky of the mind. The seer Long Darkness tells us of the cow-Word standing at the summit of Heaven and flowing with the milk of visionary light. Thus we are presented with an image similar to the one in Patanjali's Pole Star sutra, except that in the Highest Heaven we find the Word instead of a star standing still, abiding.

When awareness abides, it can see into the heart of things. The attention of the seer, fixed in the Word abiding in the Highest Heaven, flows with the following vision. He beholds an immense shaft of fire that extends through the entire universe. Along this axle seven celestial wheels revolve, yoked to the pole by spokes. Each wheel makes a separate tone. These seven tones are the songs of seven virgins who dwell in this tree, chanting seven secret words. And at the crown of the structure presides the self-luminous Word. It is said that two birds dwell in this tree. But only one of them is able to ascend to the top and eat the sweet fig there. This symbolism, as we shall see, is found also in archaic Siberian shamanism. When a young shaman is initiated, he or she must ascend a post or tree. To reach the top is to reach the center of the universe and to achieve ecstasy.

According to the seer Long Darkness, language both conceals and reveals this tree.

The Axle Tree grew also in ancient Greece, where we find a graphic description by Plato in the myth of Er, which appears near the end of his Republic. In this myth Er dies, ascends in Heaven, and then returns to his body to tell of his experiences. He speaks of the realm of Ideal Forms, the true and real Forms of which the named objects in the material universe are but pale shadows.

While in the realm of these Forms, Er sees a shaft of light, more luminous than a rainbow, stretching through the universe. At its summit shine the fixed stars, extending from them, the chains of Heaven, luminous belts that hand down attached to large hollow whorls. These nest into one another like bowls. On the upper surface of each circular whorl is a siren hymning a single melodious tone.

Shear cites this as evidence that the structure experienced by his subjects is innate, and argues that it is one of the Ideal Forms that Plato described.

Whether the seer resides in India, Greece, or Siberia, when the veil of ignorance lifts, the jeweled tree upon which the entire universe turns appears as a brilliant shaft of light with seven or so celestial wheels embracing all the clusters of galaxies. Often it is depicted with one or several birds at its summit, representing the ascent of the spirit.

from The Tao of Symbols by James N. Powell

.jpg)

Heidegger wrote that "to think truly is to confine oneself to a single thought which one day stands still like a star in the world's sky."

The Rigveda provides a similar statement:

On top of the distant sky there stands

The Word, encompassing all.

Dhruva, besides meaning Pole Star, can also signify a cow that stands still while being milked, the Word that stands still in the sky of the mind. The seer Long Darkness tells us of the cow-Word standing at the summit of Heaven and flowing with the milk of visionary light. Thus we are presented with an image similar to the one in Patanjali's Pole Star sutra, except that in the Highest Heaven we find the Word instead of a star standing still, abiding.

When awareness abides, it can see into the heart of things. The attention of the seer, fixed in the Word abiding in the Highest Heaven, flows with the following vision. He beholds an immense shaft of fire that extends through the entire universe. Along this axle seven celestial wheels revolve, yoked to the pole by spokes. Each wheel makes a separate tone. These seven tones are the songs of seven virgins who dwell in this tree, chanting seven secret words. And at the crown of the structure presides the self-luminous Word. It is said that two birds dwell in this tree. But only one of them is able to ascend to the top and eat the sweet fig there. This symbolism, as we shall see, is found also in archaic Siberian shamanism. When a young shaman is initiated, he or she must ascend a post or tree. To reach the top is to reach the center of the universe and to achieve ecstasy.

According to the seer Long Darkness, language both conceals and reveals this tree.

The Axle Tree grew also in ancient Greece, where we find a graphic description by Plato in the myth of Er, which appears near the end of his Republic. In this myth Er dies, ascends in Heaven, and then returns to his body to tell of his experiences. He speaks of the realm of Ideal Forms, the true and real Forms of which the named objects in the material universe are but pale shadows.

While in the realm of these Forms, Er sees a shaft of light, more luminous than a rainbow, stretching through the universe. At its summit shine the fixed stars, extending from them, the chains of Heaven, luminous belts that hand down attached to large hollow whorls. These nest into one another like bowls. On the upper surface of each circular whorl is a siren hymning a single melodious tone.

Shear cites this as evidence that the structure experienced by his subjects is innate, and argues that it is one of the Ideal Forms that Plato described.

Whether the seer resides in India, Greece, or Siberia, when the veil of ignorance lifts, the jeweled tree upon which the entire universe turns appears as a brilliant shaft of light with seven or so celestial wheels embracing all the clusters of galaxies. Often it is depicted with one or several birds at its summit, representing the ascent of the spirit.

from The Tao of Symbols by James N. Powell

There is a magic, a mystique, a reverence I call "the experience of North."

Watch kids on the shore of Lake Superior. No way would they sit and play a video game. Flailing over the deep sand they scramble up time-honoured protrusions of rock. They grasp the gnarled trunks of pine and spruce sculpted by the wind. They balance along ledges and shriek with delight, soon to toss off shoes and socks, maybe jeans and shirt, to pick Technicolor rocks from the diamond-clear water. Their very being understands the biblical phrase "water of life."

For adults, something intangible is found in breathing the mist from a turbulent waterfall, hearing the fugue of sound as waves break in sequence along a wind-blown shore, being absorbed by what seems ineffable. Here is a dimension of existence unrecognized in daily living: pure being, the eternal present, participation in the universe.

Others have attempted to describe this experience. Glenn Gould tried in his CBC radio program The Idea of North. John Flood, publisher of the small Penumbra Press in Manotick, Ont., has a criterion for publishing he calls northness.

The written interpretation of this feeling, the stories, adventures and personalities involved with the place that generates this northness, is a genre, a class or category of artistic endeavour, but it has no name. It is largely unrecognized, not heard, the Cassandra of literature.

Happily, Giller Prize-winning author Elizabeth Hay with her Late Nights on Airhas drawn attention to "the experience of North" as have authors Jane Urquhart, Wayland Drew, Charles Wilkins and Morley Torgov, the latter's double-entendre title, A Good Place to Come From, capturing its ambivalence.

Yet, without more recognition of this nameless literature, a part of us is being lost. The literature of the "experience of North" taps into the elusive world of wants, wonders and search for meaning. In pioneering times, literature portrayed the garrison mentality and its fear of the enemies, including nature. Now, a realization is developing that nature is no longer the enemy. Human ineptness is. Ms. Hay's Ralph did not drown because of a big, bad world out there.

A literature of "the experience of North" would delve into how the region of the Great Lakes, so important to the continent, so significant in world geography, is shaping its people. How its people are shaping the land. Only literature can tell.

Without literary articulation, the events and experiences of northness will remain buried in our collective soul, unrecognized, unexamined and forgotten.

I partly understand the difficulty in finding a name for the genre. The nebulous North is not a place. It is a feeling.

Joan Skelton is playwright and author of The Survivor of the

Edmund Fitzgerald. She lives on the shore of Lake Superior outside Thunder Bay. .jpg)

'The Pole of Relative Inaccessibility is "that imaginary point on the Arctic Ocean farthest from land in any direction". It is a navigator's paper point contrived to console Arctic explorers who, after Peary & Henson reached the North Pole in 1909, had nowhere special to go. There is a Pole of Relative Inaccessibility on the Antarctic continent, also; it is that point of land farthest from salt water in any direction. The Absolute is the Pole of Relative Inaccessibility located in metaphysics. After all, one of the few things we know about the Absolute is that it is relatively inaccessible. It is that point of spirit farthest from every accessible point of spirit in all directions. Like the others, it is a Pole of the Most Trouble. It is also - I take this as given - the pole of great price' (Dillard 1988: 19).

“It is for the Pole of Relative Inaccessibility I am searching, and have been searching, in the mountains and along the seacoasts for years. The aim of this expedition is, as Pope Gregory put it in his time, “To attain to somewhat of the unencompassed light, by stealth, and scantily.” How often have I mounted this same expedition, has my absurd barque set out half-caulked for the Pole?”

'My name is Silence. Silence is my bivouac, and my supper sipped from bowls. I robe myself mornings in loose strings of stones. My eyes are stones; a chip from the pack ice fills my mouth. My skull is a polar basin; my brain pan grows glaciers, and icebergs, and grease ice, and floes. The years are passing here' (Dillard 1988: 49).

'One wonders, after reading a great many such firsthand accounts, if polar explorers were not somehow chosen for the empty and solemn splendor of their prose style - or even if some eminent Victorians, examining their own prose styles, realised, perhaps dismayed, that from the look of it, they would have to go in for polar exploration' (Dillard 1988: 22-3).

'Wherever we go, there seems to be only one business at hand - that of finding workable compromises between the sublimity of our ideas and the absurdity of the fact of us ... I have, I say, set out again. The days tumble with meanings. The corners heap up with poetry; whole unfilled systems litter the ice ...' (Dillard 1988: 30, 47).

KNOWLEDGE WANDERED NORTH

Chuang Tzu

KNOWLEDGE WANDERED NORTH to the banks of the Black Waters, climbed the Knoll of Hidden Heights, and there by chance came upon Do-Nothing-Say-Nothing. Knowledge said to Do-Nothing-Say-Nothing, "There are some things I'd like to ask you. What sort of pondering, what sort of cogitation does it take to know the Way? What sort of surroundings, what sort of practices does it take to find rest in the Way? What sort of path, what sort of procedure will get me to the Way?"

Three questions he asked, but Do-Nothing-Say-Nothing didn't answer. It wasn't that he just didn't answer - he didn't know how to answer!

Knowledge, failing to get any answer, returned to the White Waters of the south, climbed the summit of Dubiety Dismissed, and there caught sight of Wild-and-Witless. Knowledge put the same questions to Wild-and-Witless. "Ah - I know!" said Wild-and-Witless. "And I'm going to tell you." But just as he was about to say something, he forgot what it was he was about to say.

Knowledge, failing to get any answer, returned to the imperial palace, where he was received in audience by the Yellow Emperor, and posed his questions. The Yellow Emperor said, "Only when there is no pondering and no cogitation will you get to know the Way. Only when you have no surroundings and follow no practices will you find rest in the Way. Only when there is no path and no procedure can you get to the Way."

Knowledge said to the Yellow Emperor, "You and I know, but those other two that I asked didn't know. Which of us is right, I wonder?"

The Yellow Emperor said, "Do-Nothing-Say-Nothing - he's the one who is truly right. Wild-and-Witless appears to be so. But you and I in the end are nowhere near it. Those who know do not speak; those who speak do not know. Therefore the sage practices the teaching that has no words.1 The Way cannot be brought to light; its virtue cannot be forced to come. But benevolence - you can put that into practice; you can discourse 2 on righteousness, you can dupe one another with rites. So it is said, When the Way was lost, then there was virtue; when virtue was lost, then there was benevolence; when benevolence was lost, then there was righteousness; when righteousness was lost, then there were rites. Rites are the frills of the Way and the forerunners of disorder.3 So it is said, He who practices the Way does less every day, does less and goes on doing less, until he reaches the point where he does nothing, does nothing and yet there is nothing that is not done.'' Now that we've already become `things,' if we want to return again to the Root, I'm afraid we'll have a hard time of it! The Great Man - he's the only one who might find it easy.

"Life is the companion of death, death is the beginning of life. Who understands their workings? Man's life is a coming-together of breath. If it comes together, there is life; if it scatters, there is death. And if life and death are companions to each other, then what is there for us to be anxious about?

"The ten thousand things are really one. We look on some as beautiful because they are rare or unearthly; we look on others as ugly because they are foul and rotten. But the foul and rotten may turn into the rare and unearthly, and the rare and unearthly may turn into the foul and rotten. So it is said, You have only to comprehend the one breath that is the world. The sage never ceases to value oneness."

Knowledge said to the Yellow Emperor, "I asked Do-Nothing-Say-Nothing and he didn't reply to me. It wasn't that he merely didn't reply to me - he didn't know how to reply to me. I asked Wild-and-Witless and he was about to explain to me, though he didn't explain anything. It wasn't that he wouldn't explain to me - but when he was about to explain, he forgot what it was. Now I have asked you and you know the answer. Why then do you say that you are nowhere near being right?"

The Yellow Emperor said, "Do-Nothing-Say-Nothing is the one who is truly right - because he doesn't know. Wild-and-Witless appears to be so - because he forgets. But you and I in the end are nowhere near it - because we know."

Wild-and-Witless heard of the incident and concluded that the Yellow Emperor knew what he was talking about.

Heaven and earth have their great beauties but do not speak of them; the four seasons have their clear-marked regularity but do not discuss it; the ten thousand things have their principles of growth but do not expound them. The sage seeks out the beauties of Heaven and earth and masters the principles of the ten thousand things. Thus it is that the Perfect Man does not act, the Great Sage does not move - they have perceived [the Way of ] Heaven and earth, we may say. This Way, whose spiritual brightness is of the greatest purity, joins with others in a hundred transformations. Already things are living or dead, round or square; no one can comprehend their source, yet here are the ten thousand things in all their stir and bustle, just as they have been since ancient times. Things as vast as the Six Realms have never passed beyond the border [of the Way]; things as tiny as an autumn hair must wait for it to achieve bodily form. There is nothing in the world that does not bob and sink, to the end of its days lacking fixity. The yin and yang, the four seasons follow one another in succession, each keeping to its proper place. Dark and hidden, [the Way] seems not to exist and yet it is there; lush and unbounded, it possesses no form but only spirit; the ten thousand things are shepherded by it, though they do not understand it - this is what is called the Source, the Root. This is what may be perceived in Heaven.

Nieh Ch'ueh asked P'i-i about the Way. P'i-i said, "Straighten up your body, unify your vision, and the harmony of Heaven will come to you. Call in your knowledge, unify your bearing, and the spirits will come to dwell with you. Virtue will be your beauty, the Way will be your home, and, stupid as a newborn calf, you will not try to find out the reason why."

Before he had finished speaking, however, Nieh Ch'ueh fell sound asleep. P'i-i, immensely pleased, left and walked away, singing this song:

Body like a withered corpse,

mind like dead ashes,

true in the realness of knowledge,

not one to go searching for reasons,

dim dim, dark dark,

mindless, you cannot consult with him:

what kind of man is this

Shun asked Ch'eng, "Is it possible to gain possession of the Way?”

"You don't even have possession of your own body - how could you possibly gain possession of the Way!"

"If I don't have possession of my own body, then who does?" said Shun.

"It is a form lent you by Heaven and earth. You do not have possession of life - it is a .harmony lent by Heaven and earth. You do not have possession of your inborn nature and fate they are contingencies lent by Heaven and earth. You do not have possession of your sons and grandsons - they are castoff skins lent by Heaven and earth. So it is best to walk without knowing where you are going, stay home without knowing what you are guarding, eat without knowing what you are tasting. All is the work of the Powerful Yang5 in the world. How then could it be possible to gain possession of anything?"

Confucius said to Lao Tan, "Today you seem to have a moment of leisure - may I venture to ask about the Perfect Way?"

Lao Tan said, "You must fast and practice austerities, cleanse and purge your mind, wash and purify your inner spirit, destroy and do away with your knowledge. The Way is abstruse and difficult to describe. But I will try to give you a rough outline of it.

"The bright and shining is born out of deep darkness; the ordered is born out of formlessness; pure spirit is born out of the Way. The body is born originally from this purity,6 and the ten thousand things give bodily form to one another through the process of birth. Therefore those with nine openings in the body are born from the womb; those with eight openings are born from eggs. [In the case of the Way] there is no trace of its coming, no limit to its going. Gateless, room-less, it is airy and open as the highways of the four directions. He who follows along with it will be strong in his four limbs, keen and penetrating in intellect, sharp-eared, bright-eyed, wielding his mind without wearying it, responding to things without prejudice. Heaven cannot help but be high, earth cannot help but be broad, the sun and moon cannot help but revolve, the ten thousand things cannot help but flourish. Is this not the Way?

"Breadth of learning does not necessarily mean knowledge; eloquence does not necessarily mean wisdom - therefore the sage rids himself of these things. That which can be increased without showing any sign of increase; that which can be diminished without suffering any diminution - that is what the sage holds fast to. Deep, unfathomable, it is like the sea; tall and craggy,7 it ends only, to begin again, transporting and weighing the ten thousand things without ever failing them. The `Way of the gentleman' [which you preach] is mere superficiality, is it not? But what the ten thousand things all look to for sustenance, what never fails them - is this not the real Way?

"Here is a man of the Middle Kingdom, neither yin nor yang, living between heaven and earth. For a brief time only, he will be a man, and then he will return to the Ancestor. Look at him from the standpoint of the Source and his life is a mere gathering together of breath. And whether he dies young or lives to a great old age, the two fates will scarcely differ - a matter of a few moments, you might say. How, then, is it worth deciding that Yao is good and Chieh is bad?

"The fruits of trees and vines have their patterns and principles. Human relationships too, difficult as they are, have their relative order and precedence. The sage, encountering them, does not go against them; passing beyond, he does not cling to them. To respond to them in a spirit of harmony - this is virtue; to respond to them in a spirit of fellowship - this is the Way. Thus it is that emperors have raised themselves up and kings have climbed to power.

"Man's life between heaven and earth is like the passing of a white colt glimpsed through a crack in the wall-whoosh!-and that's the end. Overflowing, starting forth, there is nothing that does not come out; gliding away, slipping into silence, there is nothing that does not go back in. Having been transformed, things find themselves alive; another transformation and they are dead. Living things grieve over it, mankind mourns. But it is like the untying of the Heaven-lent bow-bag, the unloading of the Heaven-lent satchel - a yielding, a mild mutation, and the soul and spirit are on their way, the body following after, on at last to the Great Return.

"The formless moves to the realm of form; the formed moves back to the realm of formlessness. This all men alike understand. But it is not something to be reached by striving. The common run of men all alike debate how to reach it. But those who have reached it do not debate, and those who debate have not reached it. Those who peer with bright eyes will never catch sight of it. Eloquence is not as good as silence. The Way cannot be heard; to listen for it is not as good as plugging up your ears. This is called the Great Acquisition."

Master Tung-kuo8 asked Chuang Tzu, "This thing called the Way - where does it exist?"

Chuang Tzu said, "There's no place it doesn't exist."

"Come," said Master Tung-kuo, "you must be more specific!"

"It is in the ant."

"As low a thing as that?"

"It is in the panic grass."

"But that's lower still!"

"It is in the tiles and shards."

"How can it be so low?"

"It is in the piss and shit!"

Master Tung-kuo made no reply.

Chuang Tzu said, "Sir, your questions simply don't get at the substance of the matter. When Inspector Huo asked the superintendent of the market how to test the fatness of a pig by pressing it with the foot, he was told that the lower down on the pig you press, the nearer you come to the truth. But you must not expect to find the Way in any particular place - there is no thing that escapes its presence! Such is the Perfect Way, and so too are the truly great words. `Complete,' `universal,' `all-inclusive' - these three are different words with the same meaning. All point to a single reality.

"Why don't you try wandering with me to the Palace of Not-Even-Anything - identity and concord will be the basis of our discussions and they will never come to an end, never reach exhaustion. Why not join with me in inaction, in tranquil quietude, in hushed purity, in harmony and leisure? Already my will is vacant and blank. I go nowhere and don't know how far I've gotten. I go and come and don't know where to stop. I've already been there and back, and I don't know when the journey is done. I ramble and relax in unbordered vastness; Great Knowledge enters in, and I don't know where it will ever end.

"That which treats things as things is not limited by things. Things have their limits - the so-called limits of things. The unlimited moves to the realm of limits; the limited moves to the unlimited realm. We speak of the filling and emptying, the withering and decay of things. [The Way] makes them full and empty without itself filling or emptying; it makes them wither and decay without itself withering or decaying. It establishes root and branch but knows no root and branch itself; it determines when to store up or scatter but knows no storing or scattering itself."

Ah Ho-kan and Shen Nung were studying together under Old Lung Chi.9 Shen Nung sat leaning on his armrest, the door shut, taking his daily nap, when at midday Ah Ho-kan threw open the door, entered and announced, "Old Lung is dead!"

Shen Nung, still leaning on the armrest, reached for his staff and jumped to his feet. Then he dropped the staff with a clatter and began to laugh, saying, " My Heaven-sent Master - he knew how cramped and mean, how arrogant and willful I am, and so he abandoned me and died. My Master went off and died without ever giving me any wild words to open up my mind!"

Yen Kang-tiao, hearing of the incident, said, "He who embodies the Way has all the gentlemen of the world flocking to him. As far as the Way goes, Old Lung hadn't gotten hold of a piece as big as the tip of an autumn hair, hadn't found his way into one ten-thousandth of it - but even he knew enough to keep his wild words stored away and to die with them unspoken. How much more so, then, in the case of a man who embodies the Way! Look for it but it has no form, listen but it has no voice. Those who discourse upon it with other men speak of it as dark and mysterious. The Way that is discoursed upon is not the Way at all! "

At this point, Grand Puritv asked No-End, "Do you understand the Way?"

"I don't understand it," said No-End.

Then he asked No-Action, and No-Action said, "I understand the Way."

"You say you understand the Way - is there some trick to it.

"There is."

"What's the trick?"

No-Action said, "I understand that the Way can exalt things and can humble them; that it can bind them together and can cause them to disperse.10 This is the trick by which I understand the Way.'

Grand Purity, having received these various answers, went and questioned No-Beginning, saying, "If this is how it is, then between No-End's declaration that he doesn't understand, and No-Action's declaration that he does, which is right and which is wrong?"

No-Beginning said, "Not to understand is profound; to understand is shallow. Not to understand is to be on the inside; to understand is to be on the outside."

Thereupon Grand Purity gazed up11 and sighed, saying, "Not to understand is to understand? To understand is not to understand? Who understands the understanding that does not understand?"

No-Beginning said, "The Way cannot be heard; heard, it is not the Way. The Way cannot be seen; seen, it is not the Way. The Way cannot be described; described, it is not the Way. That which gives form to the formed is itself formless - can you understand that? There is no name that fits the Way."

No-Beginning continued, "He who, when asked about the Way, gives an answer does not understand the Way; and he who asked about the Way has not really heard the Way explained. The Way is not to be asked about, and even if it is asked about, there can be no answer. To ask about what cannot be asked about is to ask for the sky. To answer what cannot be answered is to try to split hairs. If the hair-splitter waits for the sky-asker,12 then neither will ever perceive the time and space that surround them on the outside, or understand the Great Beginning that is within. Such men can never trek across the K'un-lun, can never wander in the Great Void!" 13

Bright Dazzlement asked Non-Existence, "Sir, do you exist or do you not exist?" Unable to obtain any answer, Bright Dazzlement stared intently at the other's face and form - all was vacuity and blankness. He stared all day but could see nothing, listened but could hear no sound, stretched out his hand but grasped nothing. "Perfect!" exclaimed Bright Dazzlement. "Who can reach such perfection? I can conceive of the existence of nonexistence, but not of the nonexistence of nonexistence. Yet this man has reached the stage of the nonexistence of nonexistence.14 How could I ever reach such perfection!"

The grand marshal's buckle maker was eighty years old, yet he had not lost the tiniest part of his old dexterity. The grand marshal said, "What skill you have! Is there a special way to this?"

"I have a way.15 From the time I was twenty I have loved to forge buckles. I never look at other things - if it's not a buckle, I don't bother to examine it."

Using this method of deliberately not using other things, he was able over the years to get some use out of it. And how much greater would a man be if, by the same method, he reached the point where there was nothing that he did not use! All things would come to depend on him.

Jan Ch'iu asked Confucius, "Is it possible to know anything about the time before Heaven and earth existed?"

Confucius said, "It is - the past is the present."

Jan Ch'iu, failing to receive any further answer, retired. The following day he went to see Confucius again and said, "Yesterday I asked if it were possible to know anything about the time before Heaven and earth existed, and you, Master, replied, `It is - the past is the present.' Yesterday that seemed quite clear to me, but today it seems very obscure. May I venture to ask what this means?"

Confucius said, "Yesterday it was clear because your spirit took the lead in receiving my words. Today, if it seems obscure, it is because you are searching for it with something other than spirit, are you not? There is no past and no present, no beginning and no end. Sons and grandsons existed before sons and grandsons existed - may we make such a statement?"

Jan Ch'iu had not replied when Confucius said, "Stop! - don't answer! Do not use life to give life to death. Do not use death to bring death to life." Do life and death depend upon each other? Both have that in them which makes them a single body. There is that which was born before Heaven and earth, but is it a thing? That which treats things as things is not a thing. Things that come forth can never precede all other things, because there were already things existing then; and before that, too, there were already things existing - so on without end. The sage's love of mankind, which never comes to an end, is modeled on this principle."

Yen Yuan said to Confucius, "Master, I have heard you say that there should be no going after anything, no welcoming anything. 17 May I venture to ask how one may wander in such realms?"

Confucius said, "The men of old changed on the outside but not on the inside. The men of today change on the inside but not on the outside. He who changes along with things is identical with him who does not change. Where is there change? Where is there no change? Where is there any friction with others? Never will he treat others with arrogance. But Hsi-wei had his park, the Yellow Emperor his garden, Shun his palace, T'ang and Wu their halls.18 And among gentlemen there were those like the Confucians and Mo-ists who became `teachers.' As a result, people began using their `rights' and `wrongs' to push each other around. And how much worse are the men of today!

"The sage lives with things but does no harm to them, and he who does no harm to things cannot in turn be harmed by them. Only he who does no harm is qualified to join with other men in `going after' or `welcoming.'

"The mountains and forests, the hills and fields fill us with overflowing delight and we are joyful. Our joy has not ended when grief comes trailing it. We have no way to bar the arrival of grief and joy, no way to prevent them from departing. Alas, the men of this world are no more than travelers, stopping now at this inn, now at that, all of them run by `things.' They know the things they happen to encounter, but not those that they have never encountered. They know how to do the things they can do, but they can't do the things they don't know how to do. Not to know, not to be able to do - from these mankind can never escape. And yet there are those who struggle to escape from the inescapable - can you help but pity them? Perfect speech is the abandonment of speech; perfect action is the abandonment of action. To be limited to understanding only what is understood - this is shallow indeed!"

Sadly, I part from you;

Like a clam torn from its shell,

I go, and autumn too.

THE GORGEOUS NOTHINGS

*

Excuse

Emily and

her Atoms

The North

Star is

of small

fabric

but it

implies

much

The sailor cannot see the North

but knows the needle can.

The "hand you stretch me in the dark"

I put mine in,

and turn away.

My dying tutor told me that he would like to live till I had been a poet, but Death was much of mob as I could master, then. And when, far afterward, a sudden light on orchards, or a new fashion in the wind troubled my attention, I felt a palsy, here, the verses just relieve.

Your second letter surprised me, and for a moment, swung. I had not supposed it. Your first gave no dishonor, because the true are not ashamed. I thanked you for your justice, but could not drip the bells whose jingling cooled my tramp. Perhaps the balm seemed better, because you bled me first. I smile when you suggest that I delay "to publish," that being foreign to my thought as firmament to fin.

If fame belonged to me, I could not escape her; if she did not, the longest day would pass me on the chase, and the approbation of my dog would forsake me then. My barefoot rank is better.

You think my gait "spasmodic." I am in danger, sir. You think me "uncontrolled." I have no tribunal.

Would you have time to be the "friend" you should think I need? I have a little shape: it would not crowd your desk, nor make much racket as the mouse that dents your galleries.

If I might bring you what I do--not so frequent to trouble you--and ask you if I told it clear, 't would be control to me. The sailor cannot see the North, but knows the needle can. The "hand you stretch me in the dark" I put mine in, and turn away. I have no Saxon now:--

But, will you be my preceptor, Mr. Higginson?As if I asked a common alms,

And in my wondering hand

A stranger pressed a kingdom,

And I, bewildered, stand;

As if I asked the Orient

Had it for me a morn,

And it should lift its purple dikes

And shatter me with dawn!

.png)

-e-(-No.-391)-copy.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment